Year in, year out, savoring the savoriest of pork

If you had to choose, what is the most Vietnamese dish? If you are a Vietnamese expat, what would make your mouth water the most just thinking about? What is the food, the smell, the taste that when you see or hear some stranger is savoring, you’d immediately think, “hey, he must be my fellow countryman”?

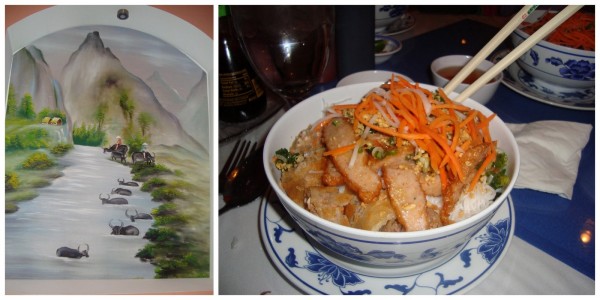

One of my friends lives in Freiburg, Germany. There is one Vietnamese restaurant 1 km away from the University, der Reis-Garten, and it is the only Vietnamese restaurant in a 40-km radius (the next one is across the border: Le Bol d’Or in Wintzenheim, France). For over 6 years living away from home, he survived on pasta and tomato sauce, students don’t have time. One day, external circumstances have finally driven him to decide that he no longer needs to suppress his cravings out of consideration towards his Germanic housemates. He bought a bottle of fish sauce. The next day he made thịt kho. That makes it official: he’s Vietnamese, and he hasn’t forgotten it.

“Success?” “Did you add coconut juice?” “Do you have eggs in the pot?” “Do you have chả lụa too?” The questions come showering on Facebook. We cheered him on with the same salivating imagination no matter which region of Vietnam we are from and where we are living: the fatty chunks of pork so tender that a plastic chopstick can cut through, the amber sauce, with which the hard boiled eggs are imbrued from yolk to white. The fatty, sweet, and salty pork must be freshened up with the crunchy, sour, cold dưa giá (pickled beansprout). The pure fish sauce makes an intoxicating savory smell that permeates the whole house, seeps through the window into the courtyard to the next door neighbor, induces a Vietnamese to lick his lips thinking of his mother’s meals and perhaps, a Westerner to cringe. But why should a cringe matter? The pure fish sauce deepens the savoriness of the meat sauce, making it the best thing to pour over a steamy bowl of white rice. My friend said all he need is this amber meat sauce and dưa giá to down a few bowlfuls. Of course, I agree.

The first weekend I got home, Little Mom sat me down in front of thịt kho, dưa giá, rice, and rice paper. All kinds of rice papers come from all over Asia, but those are for calligraphy and painting. Edible rice paper comes from Vietnam and Vietnam only. A pet peeve of mine is getting served those “spring rolls” made with wonton wrappers in American Vietnamese eateries, like a lumpia. A Vietnamese spring roll must be rolled with the translucent, veil-thin, made-of-rice-flour rice paper. Rolling it with any other kind of wrapper is an unpatriotic insult to Vietnamese cuisine. Anyway, my mom sat me down in front of her succulent slow braised pork, pickled beansprout, rice, and rice paper. Then she said go for it, and boy did I go. I made little wraps of pork and sprouts to dip into the sauce. I poured the sauce over rice. I dipped plain rice paper into the sauce. I made some more wraps and filled another rice bowl. It’s almost barbaric. The comfort of an old country taste is multiplied by the comfort of home. The eyes and tongue are no longer the principle critics, but all five senses are involved: the smell of the sauce, the sound of the sprouts collapsing between bites, the delicate touch much needed in rolling the rice paper. Each bite I took embodied the ordinary, simple, honest Southern cooking and the skillfully honed tradition of hundreds of years: thịt kho is a must-have in our Tet feast, like the turkey at Thanksgiving, the songpyeon on Chuseok, or the ozoni for Shogatsu. Well, it’s not Lunar New Year now, but it is a New Year. Maybe I’ve grown old, but I find that nothing beats celebrating the holidays at your family’s dinner table with family comfort food. 🙂

As I’m writing this post, the fireworks are going off right outside the windows, talk about food setting off fireworks ;-). Happy 2012! And may Vietnam be delicious always! 🙂