Sandwich Shop Goodies 19 – Bánh tiêu (Chinese sesame beignet)

Little Mom and I… we just have different tastes. She likes seafood. She prefers crunchy to soft. She doesn’t like sticky rice (!) She thinks the mini sponge muffins (bánh bò bông, the Vietnamese kind) are sourer than the white chewy honeycombs (bánh bò, the Chinese kind). I beg to differ. The mini sponges can be eaten alone; the honeycombs are almost always stuffed inside a hollow fried doughnut that is more savory than sweet: their sourness needs to be suppressed by the natural saltiness of oil and the airy crunch of fried batter. That doughnut, brought to us by the Chinese and called by us “bánh tiêu“, saves the honeycombs.

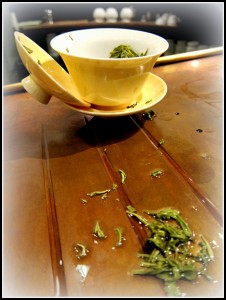

The honeycombs could go hang out with the dodo for all I care, but this Saigonese would always appreciate a well-fried bánh tiêu. At any time of the day, one would be able to spot a street cart with the signature double-shelf glass box next to a vat of dark yellow oil. The oil gets darkened from frying too many doughnuts too many times. Sure, it isn’t healthy. But should you really care about health when you eat fried dough?

“Fried dough has appeared in different forms – round, square, triangular, twisted – under many different names. The Dutch settlers had olykoeks (oily cakes); the French in Louisiana had beignets; the Spanish from Mexico made puchas de canela; and the Pennsylvania Germans made fastnachts around Lent.” (Jill MacNeice, “Doughnuts“, in the Roadside Food collection) Now I may add that the Vietnamese in California and Texas have bánh tiêu. One quality of bánh tiêu to make it superior over the other fried doughs: it isn’t coated in powder sugar. Studded with white sesame on one side, it tastes subtly salty of dough, fat, and roasted grain.

An excerpt about Vietnamese vendors making dầu cháo quẩy and bánh tiêu:

Vốc một nhúm bột khô rải đều trên bề mặt miếng gỗ đã trơn bóng – cốt để bột nhồi không bị dính – tiếp tục ngắt một cục bột đã ủ cho lên men, nhẹ nhàng vuốt dọc rồi dùng cây lăn cán qua, miếng bột đã được kéo ra thành một dây bột dài mỏng đều. Người bán lại tiếp tục dùng một thanh tre cật mỏng, xắn bột thành từng miếng đều nhau. Xếp chồng hai miếng bột lên rồi dùng một chiếc đũa ấn mạnh ở giữa, thế là đã được miếng bột “chuẩn” để làm bánh quẩy. Còn bánh tiêu thì phải qua công đoạn vốc một nắm mè vất ra giữa miếng gỗ để mè tự rải đều, sau đó mới dùng bột đã ủ đã nhồi cán thành miếng tròn dẹp, một mặt dính mè, một mặt không.

[…]

Bánh quẩy và bánh tiêu thường bán chung, có lẽ chủ yếu là vì hai loại bột làm bánh này không khác nhau là mấy. Cũng bột mì nhồi với bột khai là chính. Nhưng với bánh quẩy, người ta cho thêm chút muối, chỉ một chút thôi đủ để bánh không lạt lẽo, nhưng vẫn còn giữ được độ ngọt nguyên thủy của bột mì.

Còn với bánh tiêu, người ta lại cho thêm ít đường, cũng rất ít, đủ để làm dậy hơn vị ngọt của bột. Vị ngọt của bánh tiêu vì thế rất nhẹ, không như những loại bánh ngọt khác. Với bánh tiêu, người mua cũng không đòi hỏi phải giòn đến như bánh quẩy. Cái hấp dẫn ở bánh tiêu lại là ở những hạt mè thơm ngậy. Những hạt mè trắng li ti sau khi chiên trở nên căng mẩy, quyện với mùi thơm của bột mì chiên giòn trở nên hấp dẫn kỳ lạ. Nếu như bánh quẩy thường được cho vào dùng chung với cháo, với phở thì bánh tiêu thường được dùng kèm với bánh bò. Xẻ đôi chiếc bánh tiêu, kẹp vào giữa miếng bánh bò nữa là được một loại hương vị khác hẳn. Cái mềm xốp của bánh bò khiến bánh tiêu – vốn hơi khô – trở nên dễ ăn hơn, đỡ ngán hơn. Các loại nhân ăn kèm bánh tiêu cũng khá phong phú, tùy sở thích mỗi người. Có người mách nhau kẹp xôi vào giữa, ăn cũng rất ngon, lại có thể thay quà sáng. Có người lại thích nhân “cadé”, là loại nhân làm bằng trứng gà có vị béo ngầy ngậy, rất hợp với bánh tiêu.

Translated and abridged:

[The vendor] scoops up some flour and sprinkles them on the shining flat wooden board, to keep the dough from sticking, then he pinches off a ball of fermented dough, gently pulls it and runs the rolling pin once over to stretch the ball into a thin strip. Then he grabs a sharp bamboo stick, swiftly cuts the strip into smaller, even strips. Putting two strips on top of each other, pressing a chopstick down in the middle, and he gets a “standard” piece of bánh quẩy ready to fry. For bánh tiêu, he would need to sprinkle a pinch of sesame seeds on the board, then flatten the dough into disks, one side studded with seeds, the other side having none.

[…]

Bánh quẩy and bánh tiêu are often sold together because they have similar dough. Mainly, flour and baking soda. For bánh quẩy, they add some salt to make it savory, but not too much that it would diminish the flour’s natural sweetness. But for bánh tiêu, they would add a pinch of sugar to boost that sweetness. Bánh tiêu doesn’t have to be as crunchy as bánh quẩy either. Its goodness lies in the sesames’ fragrant nuttiness. As bánh quẩy is often eaten with rice porridge or noodle soup, bánh tiêu goes with bánh bò. Slit the bánh tiêu open, stuff in a piece of the soft white honeycomb bánh bò, and you get a whole new snack. Some people substitute bánh bò with sweet sticky rice or with egg custard, that really fattens it up.

In Saigon, Vietnam: 1000 VND each.

At Bánh Mì Ba Lẹ, Oakland: 1 USD each. (1 USD ~ 20000 VND)

Address: Bánh Mì Ba Lẹ (East Oakland)

1909 International Blvd

Oakland, CA 94606

(510) 261-9800

Previously on Sandwich Shop Goodies: steamed taro cake (bánh khoai môn hấp)

Next on Sandwich Shop Goodies: Xôi khúc (cudweed sticky rice)

Whoa – banh tieu stuffed with banh bo. Mind = blown.

1I wanna try banh tieu stuffed with xoi 😀

2Cabe ao preço de Aneel acatar essa avaliação. http://queromeudinheiro.com

3ศูนย์รักษาผู้มีบุตรยากศูนย์รักษาผู้มีบุตรยาก

โรงพยาบาลจุฬารัตน์ 11 อินเตอร์

ศูนย์รักษาผู้มีลูกยาก โรงพยาบาลจุฬารัตน์

411 อินเตอร์ : Chularat 11 IVF

Center ตั้งขึ้นด้วยความตั้งอกตั้งใจที่ช่วยทำให้คู่ครองสามารถเอาชนะอุปสรรค อันเนื่องมาจากต้นสายปลายเหตุต่างๆที่ส่งผลต่อการมีลูกยาก

โดยทีมแพทย์ผู้ที่มีความชำนาญเฉพาะด้านรักษาการมีลูกยากจากสถาบันที่เป็นที่รู้จักเป็นที่ยอมรับ

ผ่านการเรียนรู้อบรมจากในรวมทั้งเมืองนอก และมีประสบการณ์มาเป็นเวลายาวนาน รอให้คำแนะนำแล้วก็ดูแลผู้ป่วยอย่างครบวงจร โดยมีจุดประสงค์หลักเพื่อการช่วยเหลือเกื้อกูลคู่ควงที่มีปัญหาการมีบุตรยาก

ให้สามารถมีบุตรได้สมความมุ่งหมาย ด้วยบริการทางเทคโนโลยีช่วยการเจริญวัยที่มีความนำสมัยและมีมาตรฐานเป็นที่ยอมรับในระดับสากล

ศูนย์รักษาผู้มีบุตรยาก

ถ้าหากคุณสมรสมานานกว่า 1

ปี และก็มีเพศสัมพันธ์บ่อยแม้กระนั้นยังไม่ตั้งครรภ์ แปลว่าคุณกำลังอยู่ใน “ภาวะการมีลูกยาก” โดยหลักการแล้วถึงแม้ว่าสภาวะนี้จะไม่ใช่โรค แม้กระนั้นก็คือปัญหาสำหรับสามีภรรยาเป้าหมายอยากมีเจ้าตัวน้อย

เพื่อความสมบูรณ์แบบของชีวิตครอบครัว การที่คู่ชีวิตไม่อาจจะมีลูกได้อาจเป็นเพราะเนื่องจากความผิดแปลกบางสิ่งบางอย่างที่มีผลต่อภาวการณ์การเจริญวัย ทำให้ไม่สามารถที่จะมีการปฏิสนธิได้ตามธรรมชาติ โดยอาจมีสาเหตุจากข้างหญิงหรือฝ่ายชาย

หรือทั้งสองฝ่าย หรือไม่ทราบต้นสายปลายเหตุศูนย์รักษาผู้มีบุตรยาก

Yes! Finally something about bocaHickory.com.

5I feel this is one of the most significant information for me.

And i am satisfied studying your article.

However want to commentary on some common things,

6The web site taste is perfect, the articles is really

nice : D. Just right process, cheers

بدنه دستگاه قهوه ساز و جنس آن از مواردی مهم است،

که در حین استفاده اهمیتش آشکار میگردد.

این عملکرد نه تنها از سرد شدن قهوه جلوگیری

کرده بلکه از هدر رفت انرژی نیز جلوگیری خواهد نمود.

هنگام خرید دستگاه قهوه ساز این نکته

را در نظر داشته باشید، که حتماً از ترموفیوز محافظتی پشتیبانی

کند. این قابلیت بصورت اتوماتیک

عمل کرده و به هنگام ورود جریان اضافی به دستگاه، مانع

از روشن شدن دستگاه شده و از ایجاد خسارتهای احتمالی جلوگیری خواهد کرد.

سیستم ضد چکه در اکثر دستگاههای قهوه ساز امروزی یافت میشود.

میدانید که معمولاً بدنه قهوه ساز از پلاستیک میباشد و در برخی موارد شاید پوششی

از استیل بر روی آن کشیده شود.

یکی از سیستمها و عملکردهای خاصی

که معمولاً قهوه سازها و چای سازها از آن پشتیبانی میکنند، قابلیت گرم نگهدارنده است.

ظرفیت مخزن آب و ظرفیت قوری در دستگاه قهوه ساز یکی

دیگر از مشخصات مهم میباشد.

در واقع صفحه گرم نگهدارنده از سرد شدن قهوه جلوگیری

7کرده و تا یک ساعت بعد از خاموش شدن دستگاه، قهوه همچنان گرم خواهد ماند.

مدرج بودن این مخزنها امکان اندازه گیری دقیق آب و قهوه

را فراهم خواهد آورد و در تهیه قهوه مرغوب بسیار موثر خواهد بود.

هر چه تعداد افراد بیشتر باشد، باید

قهوه سازی با ظرفیت مخزن آب بالاتری خریداری کرد.

این عملکرد از چکه کردن و ریزش قهوه از دستگاه

قهوه ساز جلوگیری کرده و اجازه

نمیدهد که اطراف دستگاه کثیف

شود و قهوه هدر رود. ظرفیت مناسب به شما در تهیه قهوه مرغوب متناسب با تعداد افراد کمک خواهد کرد.

یعنی قهوه سازی را بخرید، که دارای ظرفیت مناسب باشد و مناسب بودن این ظرفیت

با توجه به تعداد افراد خانواده و یا جمع

مشخص میگردد. چرا که برای گرم

کردن آن نیازی نیست مجدداً دستگاه

را روشن نمایید.

صندلی پلاستیکی پولاد – ایران صندلی

8وکیل ملکی

9It is appropriate time to make some plans for the future and it is time to

10be happy. I have read this post and if I could I desire to suggest

you few interesting things or suggestions.

Perhaps you can write next articles referring to this

article. I wish to read even more things about it!

Howdy! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about making my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have any points or suggestions? Cheers

11I’ve been surfing online greater than 3 hours as of late, but I never found any interesting article like yours. It¦s lovely price enough for me. In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made good content material as you probably did, the internet will probably be a lot more helpful than ever before.

12Hi there, after reading this amazing article i am also cheerful to share my knowledge here with colleagues.

13The world of online slots is vast and exciting. To find the best games its helpful to read guides that break down the features RTP Return to Player and volatility of different slots. This knowledge can significantly improve your chances of winning. This resource helped me a lot when I was starting out: get reliable information. Hopefully this information helps you make a better choice. Stay safe and play smart.

14Customer support is a crucial yet often ignored aspect of online casinos. A reliable casino will offer 24/7 support through live chat or email to help you with any issues. Its a sign of a professional and trustworthy operation. To see these principles in action take a look at this detailed review: discover winning techniques. The right casino can make all the difference. Do your research and trust your instincts.

15Does your website have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but,

I’d like to shoot you an email. I’ve got some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it develop over

16time.

Howdy would you mind stating which blog platform you’re using?

17I’m planning to start my own blog soon but I’m having a hard time choosing between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal.

The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something

completely unique. P.S Sorry for getting off-topic but I had to ask!

Many players overlook the importance of a good mobile experience. A top-tier online casino should have a fast intuitive app or a perfectly optimized mobile site. Being able to play your favorite games on the go is a huge advantage. You can find a complete breakdown of a great casino experience here: read the complete analysis. Thanks for reading my thoughts. I hope this perspective is useful for someone out there.

18Thank you for sharing excellent informations. Your web-site is so cool. I am impressed by the details that you’ve on this web site. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for extra articles. You, my friend, ROCK! I found simply the info I already searched everywhere and just couldn’t come across. What an ideal site.

19I always was interested in this subject and still am, appreciate it for putting up.

20I was more than happy to find this site. I wanted to

21thank you for your time for this particularly wonderful read!!

I definitely savored every bit of it and I

have you saved to fav to look at new stuff in your website.

Fantastic post however I was wanting to know if you

22could write a litte more on this topic? I’d be very grateful

if you could elaborate a little bit more. Cheers!

I am curious to find out what blog system you are

23working with? I’m experiencing some minor security

problems with my latest website and I would like to find something more safe.

Do you have any solutions?

What’s up it’s me, I am also visiting this web site daily, this web page is really

24pleasant and the visitors are really sharing nice thoughts.

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after going through some of the articles I realized it’s new to me.

25Regardless, I’m certainly pleased I came across it and I’ll be bookmarking

it and checking back often!

I was curious if you ever considered changing the page layout of your website?

26Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people

could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or

2 images. Maybe you could space it out better?

Thank you a bunch for sharing this with all people you really recognize what you are talking approximately!

27Bookmarked. Please also visit my web site =).

We may have a link change arrangement among us

certainly like your web site but you have to take a look at the spelling on several of your posts.

A number of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it

28very troublesome to tell the truth then again I will definitely come back again.

I feel that is one of the so much significant information for me.

29And i’m satisfied reading your article. But wanna statement on few general things, The site style is perfect, the articles is in point

of fact nice : D. Just right task, cheers

After I initially left a comment I seem to have clicked the -Notify me

30when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on whenever a comment is

added I recieve four emails with the exact

same comment. Is there an easy method you are able

to remove me from that service? Thanks!

My spouse and I absolutely love your blog and find most of your post’s to be just what I’m looking for. Do you offer guest writers to write content available for you? I wouldn’t mind composing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write with regards to here. Again, awesome blog!

31Simply desire to say your article is as amazing. The clarity in your post is just nice and i can assume you’re an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

32I was curious if you ever thought of changing the structure of your blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having one or two images. Maybe you could space it out better?

33You completed some nice points there. I did a search on the subject and found the majority of persons will have the same opinion with your blog.

34Everything is very open with a precise explanation of the issues.

35It was truly informative. Your website is very useful.

Many thanks for sharing!

The other day, while I was at work, my sister stole my iPad and tested to see if it can survive a twenty five foot drop, just so she can be a youtube sensation. My apple ipad is now destroyed and she has 83 views. I know this is entirely off topic but I had to share it with someone!

36I enjoy what you guys are up too. Such clever work and exposure!

37Keep up the superb works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll.

Wonderful web site. Plenty of useful information here. I am sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And certainly, thanks on your sweat!

38I was curious if you ever considered changing the page layout of your blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or 2 images. Maybe you could space it out better?

39I got good info from your blog

40Its like you learn my thoughts! You seem to grasp a lot about this, such as you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you simply can do with a few to power the message house a bit, but instead of that, that is excellent blog. A great read. I will certainly be back.

41I found your weblog web site on google and check a couple of of your early posts. Continue to keep up the very good operate. I just further up your RSS feed to my MSN Information Reader. In search of ahead to reading extra from you afterward!…

42Do you mind if I quote a few of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your website? My website is in the exact same area of interest as yours and my visitors would really benefit from some of the information you provide here. Please let me know if this alright with you. Thanks a lot!

43I have been examinating out many of your posts and it’s pretty good stuff. I will surely bookmark your website.

44Wow! Thank you! I constantly wanted to write on my website something like that. Can I include a fragment of your post to my website?

45Normally I do not read article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very forced me to try and do so! Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, quite nice article.

46My brother recommended I may like this website. He was entirely right. This put up truly made my day. You cann’t believe just how a lot time I had spent for this info! Thank you!

47I do believe all of the ideas you have introduced in your post. They’re really convincing and will certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are very quick for newbies. Could you please extend them a little from next time? Thank you for the post.

48I am also writing to make you be aware of of the wonderful discovery my cousin’s child enjoyed reading through the blog. She learned numerous things, which included what it’s like to have a wonderful helping style to let other individuals with no trouble fully understand some tricky topics. You undoubtedly did more than readers’ expectations. Thanks for showing such informative, trustworthy, informative and also easy tips on this topic to Mary.

49Very interesting info!Perfect just what I was searching for!

50